Microplastics are in all of our bodies and impacting our health

A COLUMN by Clayton “Tiger” Hulin, R.N.

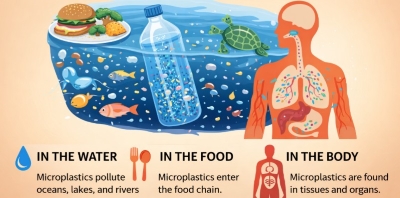

Microplastics are no longer just an environmental story. They are a human health story, and the newest research makes that clear. These tiny plastic particles, smaller than five millimeters, are now found in drinking water, soil, food, blood, and even placental tissue. They move through the body the same way any contaminant does, but they do not behave like one.

A recent study published in Environment International showed that microplastics can speed up atherosclerosis, the process that clogs arteries and leads to heart attacks and strokes. In mice already prone to the disease, males exposed to microplastics had a sixty three percent increase in plaque. The researchers found that these particles stick to the endothelial cells that line blood vessels and irritate them. Once that irritation begins, inflammation and oxidative stress follow, and plaque builds faster than it should.

That alone would be enough to raise concern. For rural communities like ours, where heart disease is common and cardiology access is limited, any added risk matters. But the next questions are just as serious. If microplastics can irritate blood vessels, what happens when they reach the brain, the kidneys, the liver, or the digestive system? Those organs do not react the same way the heart does. Many are even more sensitive.

The blood–brain barrier is one example. It protects the brain by controlling what gets in. It cannot tolerate inflammation the way the rest of the body can. Early research in animals shows that microplastics can cross this barrier and trigger inflammation inside brain tissue. The brain does not handle inflammation well. Even a small amount can affect memory, mood, decision-making, and long-term neurological health.

The kidneys face a different problem. They filter waste out of the bloodstream through delicate structures that were never meant to handle solid particles. Lab studies show that kidney cells exposed to microplastics develop inflammation and oxidative stress, which are the first steps in organ decline. For people who already have high blood pressure or diabetes, the added strain may matter more than expected.

The liver is the first organ to see anything absorbed from the digestive tract. Microplastics move from the gut to the bloodstream, and from the bloodstream to the liver. Researchers have found signs of inflammation in liver cells, along with early patterns that resemble fatty liver disease. The liver can tolerate a lot, but not constant irritation.

Then there is the digestive system, the main entry point. The gut lining absorbs nutrients, not plastic. Microplastics appear to make that lining more permeable, which allows particles and inflammatory molecules to cross into the bloodstream. They also disturb the bacteria that keep digestion balanced. That imbalance has been tied to immune problems, chronic bowel issues, and metabolic changes.

So the pattern is the same across the body.

The heart reacts with plaque.

The brain reacts with inflammation.

The kidneys react with stress.

The liver reacts with damage.

The gut reacts with disruption.

None of this means plastic alone causes these diseases. But it adds weight to systems that are already carrying a load.

This is where the story shifts from health research to a personal memory. Glass was not perfect, but I remember drinking juice and tea from glass bottles. Brother, you are missing something special if you have never tasted that. The flavor was clean. There was no hint of the plastic notes we have all gotten used to without realizing it. No polycarb taste in the background. Just the drink itself. It reminded me how much we lost when we traded glass for convenience. We accepted the new taste because it was everywhere, but it was never better. It was only cheaper.

And that taste was exactly what it appeared to be. It was the first sign that plastic was not neutral. If a bottle could change the flavor you tasted, it was also changing what entered your body. We saw it as a small tradeoff. Now we know those same particles and chemicals show up in blood, in organs, and in places no one expected. The change in taste was harmless enough, but it pointed to a deeper truth. Plastic interacts with more than flavor. It interacts with the body.

Meanwhile, the global picture grew worse. A large share of the plastic waste produced in wealthy countries ends up in rivers and waterways in developing nations. These overwhelmed systems send streams of plastic and volatile chemicals into the oceans every year. This is not the fault of the people who live there. The waste arrives faster than their systems can handle it. As it floats, new biomes form on the plastic. Bacteria, algae, and small organisms grow on the trash and use it as a raft to travel across oceans. That raises new ethical questions. Life that never would have met in the wild now lives together on plastic, and in some cases spreads into new environments that were never prepared for it.

Plastic has shown us again and again that it does not stay where we put it. Once it enters the environment, it reshapes it. Once it enters the body, it interacts with it. What looked like savings on paper has turned into the kind of cost we never planned for.

There are no perfect answers, and there never have been. Every choice comes with a cost. But in a world like this, where we are only now learning what plastic has been doing inside our bodies, I will take what seems better for me. If a cleaner bottle, a cleaner taste, and a cleaner set of risks are on the table, that is the direction I am going.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Clay “Tiger” Hulin is a Cattaraugus County writer, Registered Nurse, and family man. You can reach him anytime, claymation_88@yahoo.com

Sources cited:

Microplastics in the Human Body (blood, placenta, organs)

Luo, Q. (2025). Review: Microplastics as an emerging threat to human health. Science of The Total Environment. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0301479725018912?utm_source=chatgpt.com

– Reviews evidence that microplastics have been detected in human tissues including placenta, blood, gastrointestinal tract, lungs, and reproductive organs (APA encourages stating journal if online).

Leonard, S. V. L., et al. (2024). Microplastics in human blood: Polymer types and characteristics. PubMed. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38761430/

– Documents specific polymer types of microplastics found in whole human blood.

Ragusa, A., et al. (2021). Plasticenta: First evidence of microplastics in human placenta. Environmental Research, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0160412020322297

– Found microplastic fragments in human placentas using Raman microspectroscopy.

Campen, M. (2025). Bioaccumulation of microplastics in decedent human brains. Nature Medicine. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-024-03453-1

– Shows microplastics detected in human brains, liver, and kidneys with higher concentrations in brain tissue.

Routes of Exposure & General Health Concerns

Yee, M. S.-L., et al. (2025). Microplastics and human health. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Microplastics_and_human_health

– Overview of exposure pathways (ingestion, inhalation, dermal contact) and potential for microplastics to reach organs.

Lee, Y. (2023). Health effects of microplastic exposures: Current issues. PubMed Central. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10151227/

– Discusses complex and variable health effects of microplastic exposure and the need for further research.

Cardiovascular & Systemic Health Effects

Zheng, H., et al. (2024). Microplastics and nanoplastics in cardiovascular disease — a review. PubMed Central. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11499192/

– Reviews evidence linking micro/nanoplastics exposure with cardiovascular disease outcomes.

Organ-Specific Impacts (brain, digestive, kidney)

Ali, N. (2024). The potential impacts of micro- and nano-plastics on human health. eBioMedicine. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/ebiom/article/PIIS2352-3964(23)00467-X/fulltext

– Summarizes mechanisms by which microplastics may cause oxidative stress, inflammation, and immune dysfunction. T

Tan, R. Y. (2025). The threat of microplastics to human kidney health. ScienceDirect. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0013935125013751

– Reviews evidence of potential kidney toxicity linked to microplastic exposure.

(Optional) Li, Y. (2024). Microplastics in the human body: A comprehensive review. Science of The Total Environment. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0048969724043638

– Thorough evaluation of microplastics’ distribution and mechanisms of translocation across barriers.

Digestive System & Exposure Routes

Zhu, M., et al. (2024). A Pilot Study of Nine Mother–Infant Pairs in South China. Toxics, MDPI. https://www.mdpi.com/2305-6304/12/12/850

– Finds microplastics present in placenta, cord blood, and meconium, showing ingestion through maternal exposure.

Environmental Spread & Bioaccumulation Context

Encyclopaedia entry. Plastic pollution. (2025). Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plastic_pollution

– Notes widespread human exposure including microplastic in blood from environmental pollution.

Plastisphere. (2025). Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plastisphere

– Describes how plastic debris creates ecosystems and can transport organisms across environments.